Are Schools the Answer? Probing Phule Film’s Portrayal of Education

Phule is among a handful of films that you might see in INOX at Jio Mall that shows and names Brahmin men as the group stopping girls from learning to read and write, where tickets and popcorn sell for Rs 500 + GST. It also shows Brahim men in court challenging Mahatma Jotirao and Savitrima Phule’s removal of Brahmins from solemnising marriages. These practices made it to the film. However, the censor board and Brahmin activist groups—that might as well be the same group—stopped the film from being released. The filmmakers made several edits to the film and it was then released. This note, therefore, is distorted since the version of the film I saw has been distorted. I still want to delve into the film’s representation of schools. Brahmin men worked hard to prevent other groups from accessing the ability to read and write. A minority were able to overcome these restrictions. In the film, Jotirao’s father worked as a florist under the Peshwa Regime and was given the last name Phule and plot of land by the Regime. This mobility enabled Jotirao to enrol in a Scottish Missionary School and thereafter teach Savitrima what he had learned in school. Together, they start running a clandestine school. The camera pans to reveal three classes running simultaneously with hopeful and optimistic music in the background showing students sitting in rows with the students repeating what they are told by the teachers. After a Brahmin group finds out about the school, they enter and attack Jotirao while he is teaching and vandalise their classrooms. The Brahmin group threatens seizing their property and killing him through the village panchayat. They argued that British education would enslave Indians to the British and that Jotirao could be tried for being desh-droh and dharam-droh (anti-country and anti-religious) if he did not stop. Under such circumstances, Jotirao and Savitrima decide to leave home and go to Jotirao’s classmate’s home–Usman Shaikh.

Usman and his sister Fatima Shaikh are pleased to meet Jotirao and Savitrima. They deepen their friendship over time. After hearing their struggles, Usman and Fatima also become keen to establish the school and are prepared to offer their space to conduct classes despite the risks involved. They identify that one reason parents did not want to send their girls to school was because male teachers were teaching female students. They travel to an American missionary teacher training institute and request the principal to enrol Savitrima and Fatima. The principle says that they cannot admit students without a 10th standard completion certificate. The institute would not compromise on this rule. They pleaded and tried to make their case. Previously, Jotirao and Usman had taught both Savitrima and Fatima to read and write in English. Girls and women were not allowed to access formal education in India making it impossible to gain the necessary qualification. They would stay ineligible to become trained teachers. Without women teachers, parents and guardians will not send their daughters to schools, they argued. The cycle would continue unless the rule changes. The principal relents and admits Savitrima and Fatima. Both complete the programme.

Fatima and Usman Sheikh, and Savitrima and Jotirao have engaged with the formal schooling system to a deep extent. Several British colonial administrators are shown supporting the Phule and Sheikh’s efforts to establish such schools for girls. The latter are not naive about British colonial support– they saw it as circumstantial and as a possible mode to convert non-Christians to Christianity. Yet, they saw schooling as a pathway towards liberation.

For a moment, let’s imagine we live in a world where schools are not assumed to be positive or negative. Based on the film alone, what would we make of the role of schools? For Jotirao, it enabled him to read Rights of Man by Thomas Paine and be employed in a school prior to leaving her parent’s home. The book furthered his belief in the equality of human beings. For Savitrima, it enabled her to spend time in the missionary school and engage with girls for prolonged periods of time. For Mukta Salve, a student in the Phule and Shaikh’s school, it enabled her to write thought-provoking anti-caste and patriarchy literature that people refer to nearly 200 years later. For girls across religions and castes, it enabled them to leave the household and spend time with other girls and women. To encourage girls to attend school, several characters say that they can become doctors or engineers if they enrol in school– a common refrain that persists to today.

Schools were not originally intended as pathways to social justice or truth-seeking. In the metropole and industrialising contexts, access to certain types of knowledge and schooling were limited to the aristocracy. To gain support for public schools, reformers pleaded with factory owners (to fund the schools through taxes and allow younger workers to leave the factory) by presenting the school as a medium to serve their needs by providing disciplined, trained, and subordinate workers. Shortly after the birth of the Phules, British colonial administrator Thomas Macaulay made a case during the 1835 discussions on the English Education Act. He argued that, that the British had limited resources and education should be used to “form a class who may be interpreters between [the British] and the millions whom we govern—a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect” (Macaulay 1835). Colonial schooling aimed to control native populations and delegitimize existing knowledge systems.

Looking closely at one scene can help us understand how the filmmakers see the role of education. Phule visits the head of a wrestling training center, an influential figure, to win his support to allow girls enrol in their schools. The wrestler calls Jotirao an “agent of the British” and that physical training is the way forward to contest colonial rule. Jotirao retorts that he is fighting the biggest form of slavery, (presumably the caste-patriarchal system, without naming it) and is on the side of the oppressed Indians. Jotirao says that this battle will only be possible when the marginalised castes participate in the struggle: he states in English “equality, fraternity and liberty through education.” The leader says “your argument is above my understanding” in Hindi. Jotirao says “that’s because you haven’t acquired knowledge. Would you like that the next generation also says thick brained?” in Hindi. The filmmakers reiterate a common trope about people who are not schooled—that they are not capable of thinking and that ideal resistance to colonial rule and Brahmanism will emerge through schools. I doubt if the Phules would agree with this representation of their strategy.

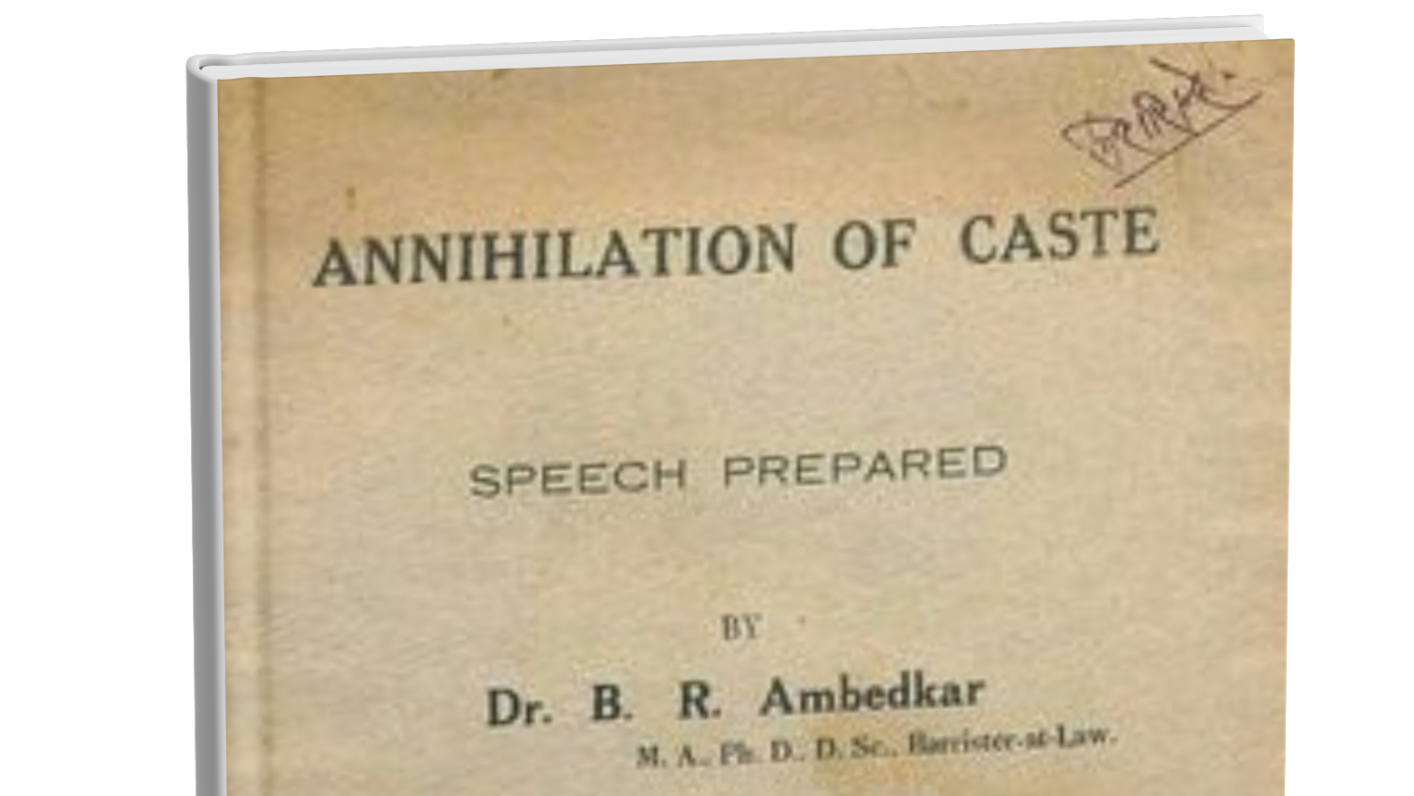

To be clear, referencing the history of colonial schooling is not to support the pre-existing caste-based system, which granted Brahmins and other Savarnas exclusive access to reading and writing while oppressing Dalits, Bahujans, NT-DNT groups, and women. Western education offered limited, yet critical, access to the Phules and later to Babasaheb Ambedkar to challenge oppressive structures. Yet, I am cautious about the uncritical expansion and celebration of schooling, as it runs counter to the Phules’ and Shaikh’s commitment to truth-seeking and social justice. Schools support the industrial-capitalist mode of production and the caste and gender based social order based on the promise that the meritorious and hard-working among the schooled will overcome structural and historical oppression and achieve “success”.

In the U.S. context, bell hooks offers an insightful critique of schools:

I loved being a student. I loved learning. … School changed utterly with racial integration. Gone was the messianic zeal to transform our minds and beings that had characterized teachers and their pedagogical practices in our all-Black schools. Knowledge was suddenly about information only. It had no relation to how one lived, behaved. It was no longer connected to antiracist struggle. Bussed to white schools, we soon learned that obedience, not a zealous will to learn, was what was expected of us (hooks, 1994, p 3).

When I first read this critique, I began to question a liberal assumption: that integration—simply removing formal separations—would improve education, rather than hide or deepen existing contempt of Savarnas, white people or men. In relation to the film, it makes me curious about the curriculum and pedagogy in the schools run by the Phules and the Shaikhs. How were teachers trained? What did alumni of their schools do? How did their approaches evolve in response to changing political and social conditions? And what were the possibilities and limitations of their approachs?

Writing this review has made me realise how much more I need to research about the history of schooling in India—especially as it intersects with industrialisation, caste, and gender. I plan to write a part two of this review, grounded in more historically supported research.

References

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Phule. Directed by Anant Mahadevan, 2025.